Substantive knowledge

The objects of study, the substantive content, is potentially vast and confusing and failure to select and organise content results in the fragmented learning of isolated nuggets of facts noted in the subject reports for Geography and History (Oftsed, 2023a&b). Making sense of the multitude of geographical and historical objects relies on applying a framework to sort content into categories that make learning efficient and meaningful. As mental representations applied to reality, those categories have the status of concepts and it is this conceptual framework that is the starting point for design in the coherent curriculum (Rata, 2019).

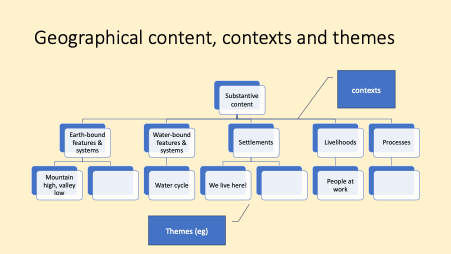

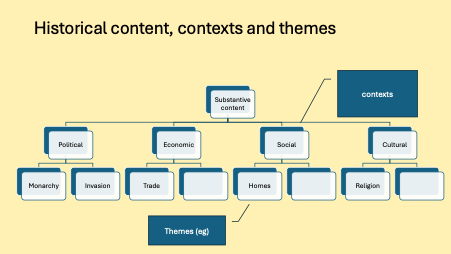

It is common to describe these categorical concepts as themes: organising ideas that run through the subject, across time and place, that offer a common framework for understanding different historical periods or geographical locations. Examples of themes from the subject association literature include ‘biomes, settlements, trade, agriculture, energy, climate, urbanisation, coasts’ for geography and ‘trade, war, government, monarchy, empire, religion, power, society’ for history.

From the subject leader’s perspective, however, themes may prove to be not so useful. Auditing provision of themes across seven year groups where individual year groups may not cover all of the chosen themes may fail to produce a clear picture of strengths and weaknesses. Themes can be a little too porous as categories and may lack clear boundaries in the conceptual framework: ‘war’, ‘invasion’ and ‘empire’ may exist separately or as nested facets of a particular event in the past. Ever-finer graded thematic strands are possible: toys, games, composting, neighbourhoods, for example, can be traced through several time periods or locations. Themes by themselves have the potential to obscure or confuse access to a meaningful overview of the subject.

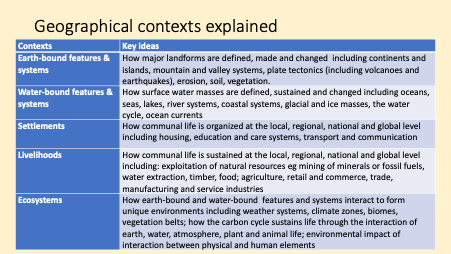

In this respect, subject contexts are more useful than themes for curriculum design, audit and revision. With a bit of tweaking of the aims set out in the NC orders these can be usefully defined in order to support subject leaders and teachers’ in their planning. For example, in Geography the traditional division between physical and human geography and geographical processes can be elaborated as five contexts: earth-bound features and systems; water-bound features and systems; settlements; livelihoods (any activity related to the sustaining of life); and processes (ecosystems):

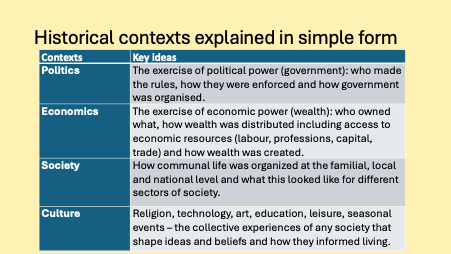

In History the contexts are derived from particular forms of history: political, economic, social and cultural:

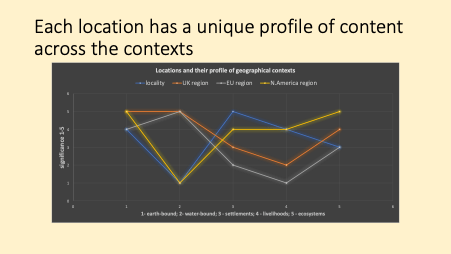

Contexts are powerful tools of analysis, too. Any geographical location or historical period can be analysed, recognised and understood in terms of its contextual profile. In other words, every location has a unique identity determined by the presence (or absence) of earth-bound, water-bound features and systems, settlements, activity related to livelihoods, and the processes at work in that location:

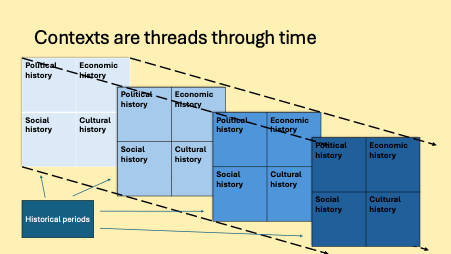

Similarly, any historical period will have its own unique profile made up of the political, economic, social and cultural conditions that define it as a particular moment in time. Contexts are the organisational lettering that runs through the substantive stick of rock:

Whilst the context is the unit of organisation most useful to the subject lead, the theme is the unit of planning that teachers and students will mostly encounter in the classroom. The connection between context and theme is not straightforward and many themes may contain elements of two or more contexts. As a tool for subject management, contexts provide a useful guide to breadth and balance in designing and auditing provision and offer a framework that supports learners as they move towards a more expert command of the subject. Themes, however, are the bridge between the abstract notion of contexts and the actual ‘stuff’ of history and geography, the facts and figures. Just as any teenager is intuitively able to locate the ice cream or juice in a crowded fridge, eventually we want learners to be able to use contexts and themes to help them make sense of the myriad facts encountered in the course of their studies.

Contexts are matched to local circumstances through the selection of themes. Deriving themes from the framework of contexts will enable subject leaders to design a local curriculum that meets the NC requirements for breadth and balance. Looking for opportunities to exploit the potential of the locality to illustrate the subject contexts allows learners to understand their circumstances in relation to the bigger pictures of geography and history at the regional, national and global levels. Similarly, exploiting the powerful encounters of first-hand experience mediated through the subject contexts prepares learners to develop later understanding of these important abstract notions through these first encounters with material evidence in the locality.

Having identified a set of themes grounded in the framework of subject contexts, the next challenge for curriculum design is to work out how those themes are expressed as continuous but progressively complex strands across the year groups. Despite the frequency at which problems of sequencing are highlighted in inspection reports, exploration of theory underpinning the sequencing of knowledge is poorly explored in Ofsted’s research activity. It is not sufficient to suggest, as the recent subject reviews do, that sequencing is the same as building on earlier knowledge and enabling later learning. These are the outcomes of sequencing not the essence which needs a better explanation than the catchphrases of progression and continuity that seem to run like a stuck record in the blogs, reports and conversations. Part three of this series will look at how subject leaders can use a framework of conceptual development derived from Vygotskian theory and research from coherent curriculum design, to structure progression in knowledge acquisition.

References

Ofsted (2023a) Rich encounters with the past: history subject report. Available at:https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/subject-report-series-history/rich-encounters-with-the-past-history-subject-report

Ofsted (2023b) Getting our bearings: geography subject report. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/subject-report-series-geography

Rata, E. (2019). Knowledge‐rich teaching: A model of curriculum design coherence. British Educational Research Journal 45(4): 681–697.